2013

SARAH MOOK

POETRY PRIZE RESULTS

6-8 FIRST PLACE

Noelle

Timberlake

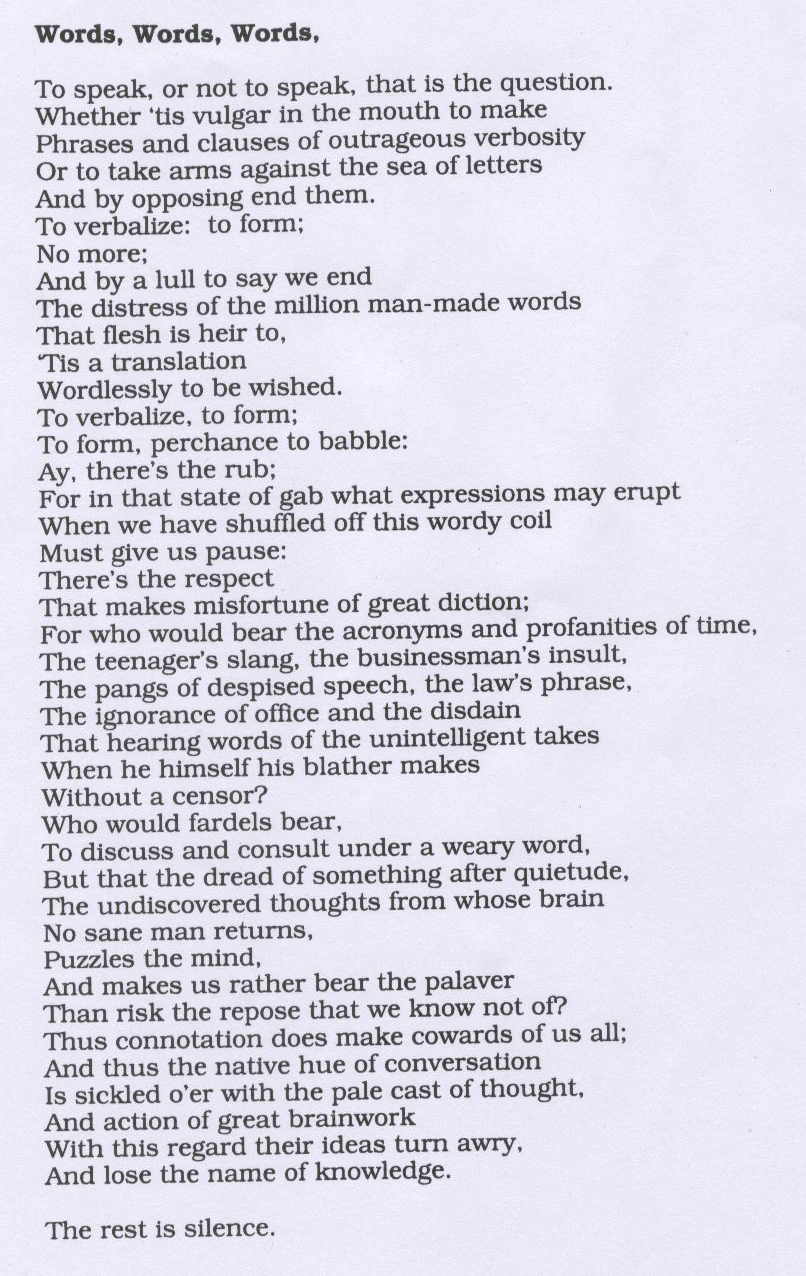

Words, Words, Words

|

|

COMMENTS FROM CONTEST JUDGE MARIE KANE: The first place poem for grades six through eight is a parody of the "To be, or not to be" soliloquy in William Shakespeare's Hamlet. The poem hits all the notes of an accomplished parody by imitating syntax, language, tone, and intent of Hamlet's famous speech to achieve a comic effect. There are many interpretations

of Hamlet's soliloquy that are textually, historically, or otherwise

based. For the sake of analysis here, we'll state that the soliloquy

explores the contemplative question of many disheartened and tortured

souls: is it better to live with life's "sea of troubles"

or to end one's sorrows with death?

The parody's lines demonstrate the writer's excellent imitation of the structural elements and tone of Hamlet's speech with comic effect:

In the parody, much of Shakespeare's syntax, diction, and meter are adhered to with great success. The young writer even parallels the original's parts of speech, with nouns of amount: "million" and "thousand," nouns that describe pain: "distress" and "heart-ache," nouns that end in 'tion': "translation" and "consummation," adverbs: "wordlessly" and "devoutly," and the all-important " 'Tis." The author smoothly incorporates into the parody the original's phrases of "No more," "to say we end," "that flesh is heir to," and "to be wish'd." The parody continues to spar with the original in the most important lines of the speech. The heart of the "To be, or not to be" soliloquy occurs from lines nine to twenty-one in which Hamlet wrestles with the dilemma of choosing life with all of its pain, verses death with all of its uncertainly. The question of what the "sleep of death" holds must be measured against life and its "whips and scorns of time," "pangs of despised love," and "law's delay." To correspond with Hamlet's lines, the author of "Words, Words, Words" superbly handles his or her own dilemma of speech or silence. Many words in the parody deal with the concept of speech; also, I've italicized the words and lines from Hamlet's soliloquy that cleverly remain.

I admire much in this section. The perceptive line, "When we have shuffled off this wordy coil," solidifies the talent of the writer. The wickedly funny lines, "That makes misfortune of great diction," and "who would bear the acronyms and profanities of time" poke fun at Hamlet's soliquoy that asks serious questions about knowledge and existence, while the parody ironically and effectively uses his very words to trivialize these matters. Retaining the exact rhyme and anastrophe in "That hearing words of the unintelligent takes / When he himself his blather makes" establishes this writer's clever adaptation. The word choice of "blather" is perfect. Also, the fact that the writer retains Shakespeare's "we" is vital; both questions are universal, not personal. I especially appreciate the comparison of having a "censor" for one's speech to Shakespeare's " bare bodkin" (suggesting a dagger) to end one's life; the sharpness of both is clear, making for a gifted parody indeed. In the last third of the soliloquy, both Hamlet and the writer of the parody make their choices. Hamlet wonders:

The parody's excellent interpretation of this internal debate follows:

The second line effectively uses the vocabulary of speech with "discuss and consult" and "word." Note the clever word choice of "quietude" instead of "death," and "brain" instead of "bourn." Also, "palaver" fits the meaning of the parody humorously and exactly. Plus, to "rather bear the palaver and "risk[ing] repose that we know not of" successfully mock the internal debate of the original. In the end, Hamlet's conclusion and the writer's are similar. Hamlet states that in choosing life and its pains over death, "conscience does make cowards of us all," claiming that thought can deter action. In the parody, it is speech that causes inaction - or, in this case, silence. The writer's quandary of speech over silence is ingeniously summed up as: "Thus connotation does make cowards of us all." (Note that that both nouns begin with the letter, 'c'.) Instead of Shakespeare's "native hue of resolution," the parody presents the "native hue of conversation" which is "sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought," an astute use of Shakespeare's phrase. At the end of the soliloquy, Hamlet laments that the "enterprises of great pith and moment / With this regard their currents turn awry, / And lose the name of action. The parody expresses the upshot of "to speak, or not to speak" in this way:

For the author of "Words, Words, Words," the "blather" and "palaver" of speech is preferred to the "risk of repose" even if it means our "ideas turn awry" and we "lose the name of knowledge." The author adds this last line, "The rest is silence," as a coda to emphasize and almost mock his or her own choice of filling the air with useless words. The effect of parody

can be simply comic, but more often the imitation is the result of great

respect for the original, as I suspect it is here. This young writer

has achieved a high level of parody and humor by closely studying and

appreciating the syntax, diction, intent, and meaning of the original.

This first place winner is a perceptive reader and talented, mature

writer whose accomplished work is very enjoyable to read. Thank you for the privilege of reading your work! Marie

Kane |