2011

SARAH MOOK

POETRY PRIZE RESULTS

9-12 SECOND PLACE

Christian

Robinson

Oak Park, IL

|

|

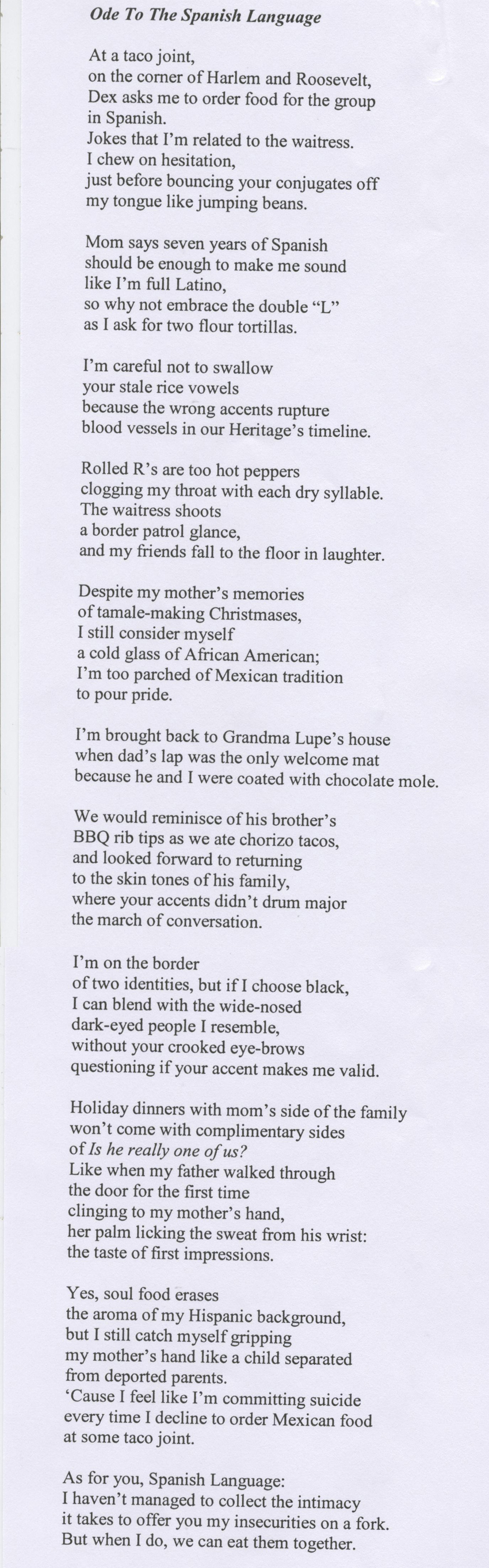

COMMENTS FROM CONTEST JUDGE MARIE KANE: A note to all finalists: You are to be congratulated on your excellent entries to the 2011 Sarah Mook Poetry Contest. What trouble I had this year in deciding the winners! Because your work was advanced on all levels, my efforts took a longer time than usual to make the final decision. Know that your poems were read with care and attention to detail. I enjoyed every one of them! Sincerely, ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ "Ode to the Spanish Language" is an imaginative and pleasurable poem to read; the entire poem is an apostrophe addressed to the language itself. It is also an extended metaphor regarding food from two cultures, and its inventive images track the speaker's desire to side with the father's African American ancestry, while still honoring the mother's language and Mexican heritage. This second place poem for this age group skillfully observes the tug of allegiance to both sides of the speaker's culture, and does so with original images, an attention to detail regarding line breaks and punctuation, and a wry tone that marks the maturity of the poem. As an ode, this poem's modernity is apparent; it has no rhyming pattern, uses casual diction, and is informal in tone. However, the pleasing use of assonance, consonance, and alliteration aids the poem's rhythm. Like all odes, it is written to and in praise of something that serves as inspiration for the poet - in this case, the Spanish language. And even though the speaker remains fearful that he or she will not be able to pronounce words as a native speaker does, or senses that doing so may betray his or her African American heritage, this poem is clearly written as an ode to the Spanish language. By the end of the poem, the speaker acknowledges that one day "insecurities" surrounding the Spanish language will be "managed." The opening section occurs at an eatery and sets the scene for the entire poem: "At a taco joint / on the corner of Harlem and Roosevelt," the speaker is asked by a friend to order food in Spanish, who also "jokes that I am related to the waitress." The speaker's response is to relate the Spanish language to her mood; she will "chew on hesitation / just before bouncing your conjugates off / my tongue like jumping beans." This metaphoric comparison is original, visual, and cleverly related to Spanish food. Also, the Spanish language is given it a voice in the poem through personification. In the next two sections, the poem continues at the "taco joint." The speaker remembers that his or her mother wants Spanish to be learned. The mother in the poem "says seven years of Spanish / should be enough to make me sound / like I'm full Latino." The speaker's bravery arises with this thought: "so why not embrace the double "L" / as I ask for two flour tortillas." Note the food references and the expert line breaks in the next sequence of lines, as the speaker has to be:

The line breaks in the above section (and throughout the poem) are masterful in their surprise and emphasis. Also note the careful lack of punctuation; many scholastic writers over punctuate poetry- this writer does not. The poem continues with more food references, along with the speaker's hesitation regarding speaking Spanish, especially in front of friends. The use of appropriate visual metaphors is pleasing:

With the "too hot peppers" of "rolled R's," and the "dry syllable[s]," the speaker's order clogs the throat. The waitress "shoots a boarder patrol glance"; since the speaker and the waitress are said to "be related" in the opening, perhaps the speaker's Spanish seems a betrayal of African American heritage, thus the warning glance. The speaker's friends "fall to the floor in laughter," perhaps evidence that our speaker has not yet mastered the nuances of pronunciation of the language. Again, the speaker is between two cultures, not fitting into either. The next section of the poem becomes reflective; it moves from the narrative to the contemplative and refers to the speaker's mixed heritage. This change of tone and mood is welcome in the poem in that it does not remain an experiential poem only, but becomes a thoughtful one as well. The speaker notes that in spite of the mother's "memories / of tamale-making Christmases," a "cold glass of African American" is at his or her center. African American culture is preferred because he or she is "too parched of Mexican tradition / to pour pride." One of the most meaningful sections in the poem is the next tercet:

Both cultures are used here and together they form a vivid image. Mexican food, again, is the important connector for this speaker. Here is the first time a father is mentioned, and both he and the speaker's skin color are related to the famed Mexican sauce spiked with chilies, spices, and a hint of bitter chocolate, thus melding both cultures in a brevity of language that pleases. African American heritage is preferred, since the father's lap, called a "welcome mat," shelters the speaker and offers a safe place in "Grandma Lupe's house." The next section continues this reminiscing. Note the use of the surprising and forceful metaphor in the last two lines:

This attempt to marry these two cultures continues to be difficult for the speaker because the "skin tones" of the father's family are preferred. At that family's home, the conversation is not marshaled or directed by the Spanish language, and the food offered seems to be more to the speaker's liking. Finally in the eighth section, the speaker forthrightly lays out the option. The direct statement of, "I'm on the border / of two identities," explains all of the earlier trepidation in the poem. The speaker presents the joint heritage as a "border" that must be crossed one way or the other, as a choice, and as an either / or situation. It is this rigid definition of choice that keeps the speaker from melding the two cultures. The poem goes on: "if I choose black," the speaker can "blend with the wide-nosed / dark-eyed people I resemble." Now we see a reason for the speaker's preference; it is appearance that sways opinion. The poem directly addresses the Spanish language and states, "without your crooked eye-brows / questioning if your accent makes me valid." By personifying the Spanish language with its "crooked eye-brows" and "questioning," the speaker demonstrates that the way to possesses validity is to master Spanish language accents. Food is again a focus in the next section with "holiday dinners." The speaker reveals the prejudice that welcomed the father into the mother's family:

Identity, placement, and distinctiveness shape the important quests for the speaker of this poem. In the next section, the speaker seems to reiterate preference for African American aspects of life. The speaker admits that "soul food erases / the aroma of my Hispanic background" but still, the mother's hand is gripped "like a child separated / from deported parents." The masterful verb "erases" and the simile of separation from deported parents, perhaps due to illegal immigration, are both sensory and visual. However, the speaker's ambivalence is apparent:

So, here, we see that both cultures have their prominence in this speaker's heart. The father's, most likely because of resemblance, and the mother's, most likely because of loyalty. In the last four lines of the poem, the speaker strikes a truce with the Spanish language:

Finally, the speaker solves the problem of the "border" between cultures: "insecurities" are "offered," "shared" on a fork, and eaten "together." This ending again employs the metaphorical language of food and eating; it is this ironic and resourceful resolution to the poem's dilemma that marks this poem a first place winner. Throughout

this masterful piece, the poet stays true to the ode form in tone of

address, (albeit rueful), uses original, often surprising, language,

and skillful poetic techniques. The energy of language is memorable,

and the writing's fearlessness is admirable. Hats off to this talented

writer. Thank you for the privilege of reading your work. Marie

Kane |